Hey Everyone!

This being my first blog of 2026, I am genuinely excited to dive into this topic and my main objective for writing this blog is to introduce you to my thought process and explain trade-offs I made along the way, I would deliberately avoid code and focus more on the fundamentals since they remain the same across all services, frameworks or languages.

Before getting into the technical story, a bit of context helps.

I was working on implementing image upload functionality for my project, Hive. The goal was simple on the surface: allow users to upload images for their content inside their workspace. If you are curious about the Hive, feel free to check it out over here. Yes, that was a shameless plug.

With that context out of the way, we can now get into how this seemingly simple requirement slowly turned into an interesting engineering problem.

Chapter 1: The "just store it in the database" phase

At the beginning, "upload an image" meant exactly what it sounds like. A user picks a file, the app sends it somewhere, and the image shows up in the app. Nothing fancy. Just make it work and move on.

That mindset comes with very convenient assumptions. Files are small. Uploads are rare. Users behave nicely. And if something breaks, the backend will somehow deal with it.

This is also where the tempting solutions appear. Store images directly in the database. Maybe encode them as base64 and save them alongside everything else. Or let the backend accept the file and upload it to storage. Centralized, simple, fast to ship.

But this falls apart once you look at real constraints.

In my case, files needed strict membership based access. They could not exist globally. Every file had to belong to a workspace and only be accessible to the right users. This is common across most real applications, driven by business logic rather than technical preference.

On top of that, this was user generated content, which means trusting the client is not an option. And to make things more interesting, most of this was running on free student hosting plans. Limited compute, strict timeouts, and zero tolerance for inefficient APIs.

Once I reasoned through this, the naive approaches started feeling wrong even before shipping. Base64 storage bloats database rows, slows queries, and turns backups into a problem. Backend mediated uploads mean long running requests, higher memory usage, and retry logic that gets messy fast.

Naive flow

Browser

|

v

Backend

|

v

Database or Object StorageThe warning signs were obvious on paper. This was not going to break loudly. It was going to break slowly and expensively. That was the signal to pause and rethink the design.

Chapter 2: Rethinking the backend's responsibility

After moving away from the "just put it in the database" mindset, the next question was uncomfortable but necessary: what should the backend actually own?

The instinctive answer is everything. Receive the file, validate it, store it, return success. That feels safe because the backend stays in control. But file uploads turn the backend into a delivery truck. It is no longer just making decisions. It is now moving large, slow, unpredictable chunks of data.

This is especially problematic in containerized or serverless environments. Short execution limits, memory caps, cold starts, and slow client connections do not mix well with multi megabyte uploads.

The responsibility split became clearer once I looked at it this way. The backend should own the rules, not the bytes. It should decide who can upload, where the file belongs, and under what constraints. It should not be in the business of transporting data.

That led to a shift from uploading files to authorizing uploads.

Instead of receiving the file, the backend issues a tightly scoped permission. One file. One location. Short expiry.

Revised flow

Browser ---> Some upload location

\

---> Backend ---> DatabaseThe backend is deliberately removed from the hot path. Requests stay small and fast. Timeouts become rare. Memory pressure disappears.

The immediate benefits were obvious. Performance improved. Reliability improved. And the system became easier to reason about because each component was doing the job it was actually good at.

The backend stopped being a transporter and became a gatekeeper.

Chapter 3: Enter object storage

Now that the backend is no longer acting as a delivery service and the database is clearly not the place for raw files, the obvious question is: who should actually handle storing and moving these files?

This is where object storage comes in.

Object storage services like Amazon S3, Cloudflare R2, Google Cloud Storage, and Azure Blob Storage exist specifically to store large files. They are built to handle big payloads, retries, and high throughput at a much lower cost than application servers or databases. They do not understand users or business logic, and that is by design. (For my application I have used Cloudflare R2 as it has most generous free tier)

Their job is simple: accept blobs, store them reliably, and serve them back when asked.

Two ways to upload files using object storage

Once object storage is part of the system, there are two realistic ways to use it for uploads.

The first approach is letting the backend upload the file to storage on behalf of the client.

Browser -> Backend -> Object StorageThis keeps everything centralized and gives the backend full visibility into the upload. But it also means large request bodies, long lived connections, higher memory usage, and retry logic that gets complicated fast. On containerized or serverless backends, this approach hits limits very quickly.

The second approach is letting the browser upload the file directly to object storage.

Browser -> Object Storage

\ /

\ /

-> Backend <-Here, the backend never touches the file bytes. It only authorizes the upload and records metadata. The actual data transfer happens directly between the browser and storage.

The trade off and why I chose direct uploads

Letting the backend upload files offers tighter control but comes at the cost of performance and reliability. A slow or flaky client can tie up backend workers and impact unrelated requests.

Letting the browser upload directly pushes the heavy work to object storage, which is built for exactly this problem. Upload speed, retries, and large payloads are handled outside the backend, keeping APIs fast and predictable.

The backend still stays in control of the rules. It decides who can upload, where the file belongs, and how long the permission is valid. It simply does not act as the middleman for moving bytes.

For this system, that trade off made the most sense.

Chapter 4: Presigned uploads and controlled access

Once the decision is made to let the browser upload files directly to object storage, the next obvious problem shows up immediately. How does the browser upload a file without having direct access to storage credentials?

You cannot ship object storage keys to the client. Those credentials are powerful and unrestricted. Anyone who has them can read, write, or delete objects. That would be a disaster.

This is where presigned URLs come in.

The backend already has secure access to the object storage service using its own credentials. It uses that access to generate a very specific, time limited permission that the browser can use exactly once.

High level idea

The backend uses its storage credentials to say:

"You are allowed to upload one file, to this exact path, for a short amount of time."

The browser never sees the real credentials. It only sees the temporary permission.

Step 1: Browser asks for permission

Browser

|

| request upload permission (filename, type, workspace)

v

BackendAt this point, no file is uploaded. The backend is only deciding whether the request is allowed.

Step 2: Backend generates a presigned URL

Backend

|

| uses storage credentials

| to generate scoped permission

v

Object Storage

|

| returns presigned URL

v

BackendThe backend signs a request using its own credentials. The object storage service validates the signature and returns a presigned URL with an expiry.

Step 3: Browser uploads using the presigned URL

Browser

|

| PUT file using presigned URL

v

Object StorageThe browser uploads the file directly to storage via a PUT HTTPS request. No backend involvement. No credentials exposed.

Why this is secure

- Storage credentials never leave the backend

- The presigned URL is:

- Time limited

- Scoped to a single object key

- Limited to a specific operation (upload)

- Even if the URL leaks, the damage is limited

The backend still controls who can generate these URLs and under what conditions.

CORS and browser access

Since the browser is uploading directly to object storage, CORS must be configured on the storage bucket.

This allows:

- Browsers to make cross origin requests to storage

- Only specific origins

- Only specific HTTP methods like PUT

- Only required headers

Without this, the upload would fail even with a valid presigned URL.

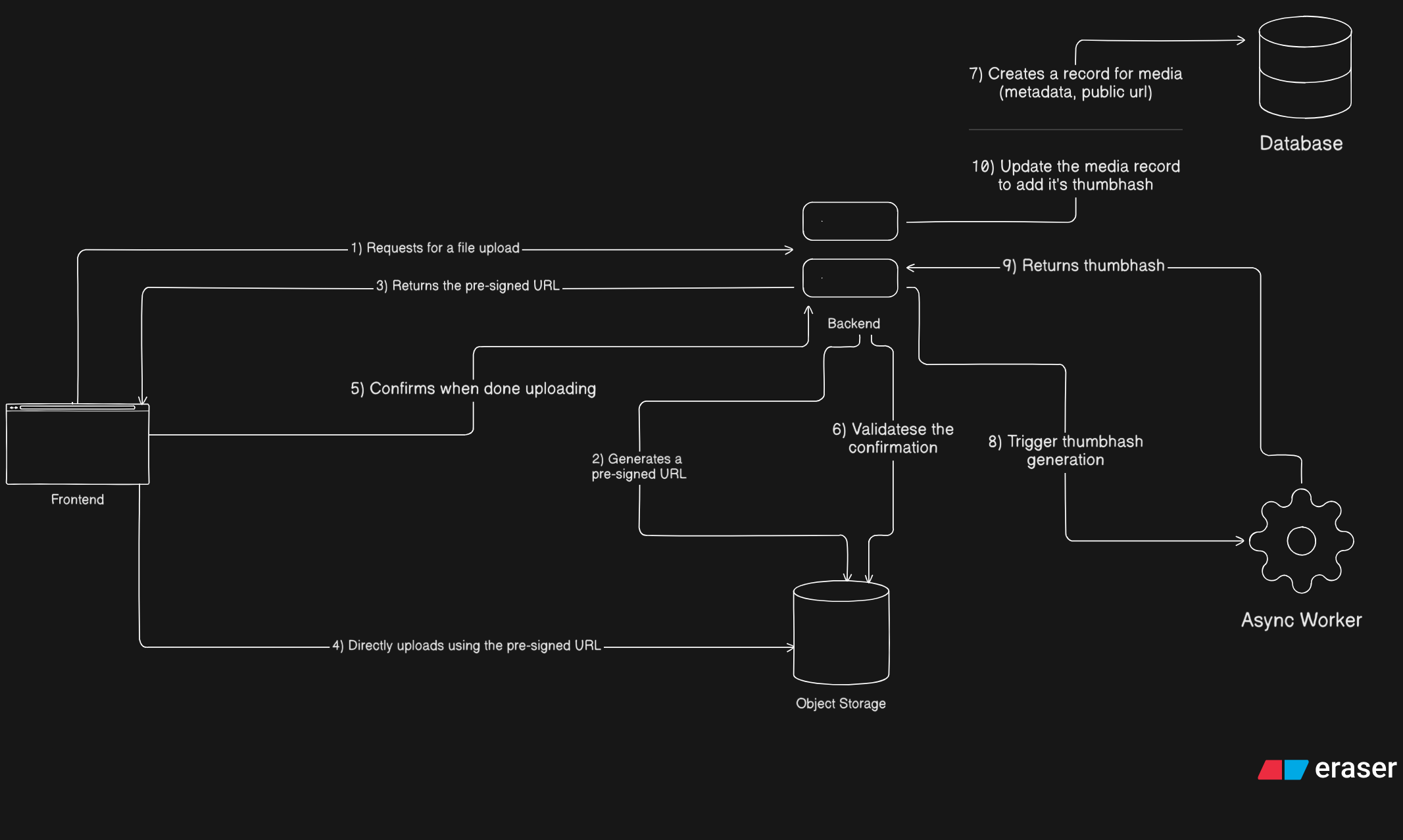

An overview

Chapter 5: Confirming uploads and dealing with ghost files

Once a file is uploaded to object storage, it technically exists. But that does not mean it exists in the system.

This distinction is important.

From the application's point of view, a file should only be considered real after the backend explicitly accepts it. Until then, it is just an object sitting in storage with no guarantees.

Why confirmation is necessary

Direct uploads introduce a simple but unavoidable problem. Uploads can succeed in storage but fail everywhere else.

- The user might close the tab.

- The network might drop.

- The confirm request might never be sent.

If the system treats every uploaded object as valid, it will slowly fill up with junk.

So instead of trusting the upload itself, the backend requires a confirmation step.

The confirmation flow

Browser

|

| confirm upload (object key, metadata)

v

Backend

|

| verify object exists

| create media record

v

DatabaseOnly after this step does the file officially exist in the application.

From this point on, the database becomes the source of truth. Storage just holds bytes.

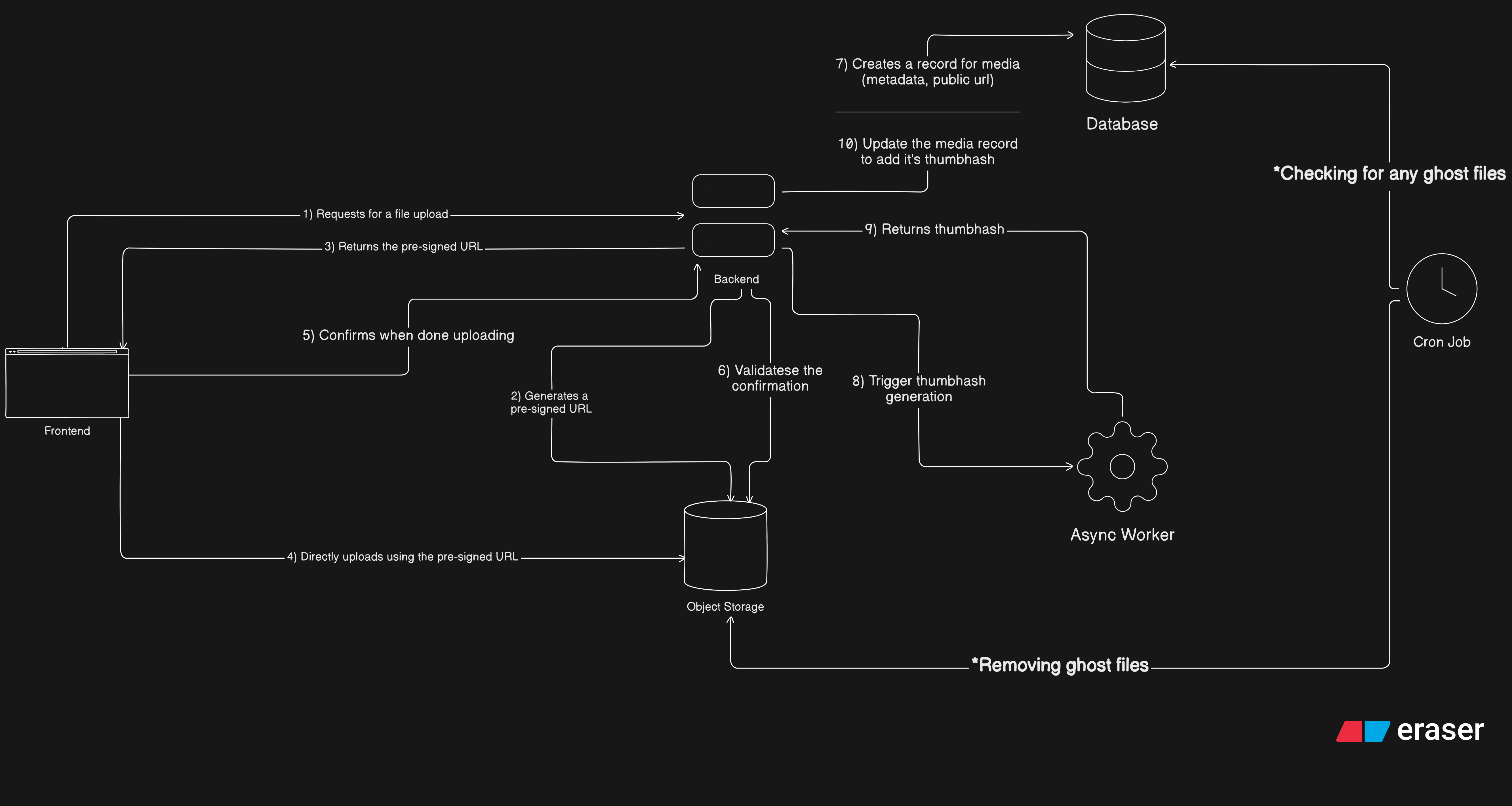

Ghost files are inevitable

Anything that reaches storage but never gets confirmed becomes a ghost file.

This is not a bug. It is a natural consequence of distributed systems and unreliable clients.

Trying to prevent ghost files entirely complicates the main upload flow and usually makes things worse. Cleaning them up later is much simpler.

Cleanup as a background job

The cleanup logic is straightforward:

- Scan object storage for files older than a grace period

- Check if they have a corresponding database record

- Delete anything that does not

In a perfect world, this runs as a scheduled cron job.

In my world, I do not have a deployed cron job yet, so I run a local script every two or three days and call it "manual automation".

It works.

Why this approach is acceptable

Ghost files are temporary. Cleanup is deterministic. The core upload flow stays simple and reliable.

Most importantly, the application never exposes unconfirmed files to users. A file either exists officially or it does not exist at all.

Chapter 6: Thumbhash and doing the extra work without slowing things down

Once the upload pipeline itself was stable, the next problem was not correctness anymore, it was experience.

Loading images directly can feel jarring. Blank spaces pop in, layouts shift, and users momentarily lose context. I wanted something lightweight that could represent an image before it actually finished loading.

This is where thumbhash comes in.

What thumbhash is

Thumbhash is a way to represent an image using a very small amount of data. Instead of storing or serving a tiny version of the image, you store a compact encoded string that roughly captures the image's colors and structure.

On the frontend, this string can be decoded into a soft, blurred placeholder that fills the space while the real image loads.

The important part is size. A thumbhash is tiny. Usually just a few dozen bytes. That makes it cheap to store, cheap to send, and fast to decode.

How thumbhash works and why base64 fits well

At a high level, thumbhash generation looks like this:

- Take the original image

- Decode it into pixels

- Extract dominant colors and rough spatial information

- Encode that information into a compact binary format

That binary data then needs to be stored and transmitted somehow. In my case, I store it as base64.

Base64 works well here because:

- The data is very small, so the size overhead does not matter

- It is easy to store directly in a database column

- It can be sent over JSON APIs without special handling

- The frontend can decode it easily

This is very different from storing full images as base64. For large files, base64 is a terrible idea as it inflates image size by about 33%. For something this small, it is perfectly fine and very convenient.

Why I did not generate thumbhashes in the main backend

At this point, it would be reasonable to ask: why not just generate the thumbhash in the backend right after upload?

I could have done that. But it would have mixed concerns in a way I wanted to avoid.

Generating a thumbhash means:

- Fetching the image from object storage

- Decoding image formats

- Running CPU heavy image processing

All of that costs time and compute.

Doing this inside the main backend would:

- Increase CPU usage on API servers

- Extend request chains

- Make uploads slower

- Tie non critical work to critical paths

And most importantly, thumbhash generation is not required for an upload to be considered successful. The image should exist even if the thumbhash never gets generated.

That made it a bad fit for the main backend.

Enter async workers

This is a classic case for asynchronous work.

In layman terms, an asynchronous (async) worker is someone who does not need to be online or available at the same time as their colleagues to collaborate and get work done. Instead of expecting immediate responses (synchronous communication, like live meetings or instant messaging), work is designed around a time lag, allowing each person to contribute to tasks and communicate on their own schedule and within a reasonable timeframe (e.g., 24 hours).

Examples of such async worker

Async workers are great for tasks that:

- Are compute heavy

- Are not user blocking

- Can fail without breaking core functionality

Instead of doing everything inline, the backend hands off the work and moves on.

Conceptually, this introduces a new role in the system:

- Backend decides and records

- Worker processes and enriches

This keeps responsibilities clean.

Why I chose Azure Functions

For the worker itself, I went with Azure Functions. Though accurately it's an event-driven serverless compute service, it can be used as an async worker by triggering it function via a message queue or event stream (in this case it's a simple HTTP trigger), allowing it to process the task independently in the background while the caller (my main backend) immediately moves on.

It fit my situation well. I already have student credits on Azure and my main backend is also hosted there, so using Functions was essentially free to experiment with.

Beyond that, Functions work nicely for this kind of task:

- They spin up only when needed

- They scale independently from the backend

- They are isolated from API traffic

- They are cheap for short lived compute

If a function fails, nothing critical breaks. The image is still uploaded. The system just misses an enhancement.

That failure isolation was exactly what I wanted.

How the thumbhash flow fits into the system

Once a media record is created, the backend triggers the async worker with just enough information to do its job.

Backend

|

| send media reference

v

Async Worker (Azure Function)The function then:

- Fetches the image from object storage

- Generates the thumbhash

- Encodes it as base64

- Sends the result back to the backend

Async Worker

|

| fetch image

| generate thumbhash

| callback with base64 hash

v

Backend

|

| update media record

v

DatabaseAll of this happens off the critical path. The user never waits for it. If it succeeds, great. If it fails, nothing breaks.

The final flow of the pipeline

Pardon my illustration skills haha

Here is the full combined text with everything included, cleanly integrated and ready to drop into your chapter.

Chapter 7: Optional work, intentional limits, and knowing when to stop

By this point, a clear pattern has emerged.

- The backend owns rules and truth

- Object storage owns bytes

- Async workers own expensive, optional compute

Thumbhash generation fits naturally into this model. It lives outside the critical path, improves experience, and does not affect correctness.

At this stage, I kept coming back to a quote by Martin Fowler:

Don't distribute your objects!

It sounds funny at first, but it is painfully accurate. Every time I felt tempted to spread responsibility across more layers or make different parts of the system aware of too much, this quote acted as a reminder. Keep boundaries tight. Keep responsibilities narrow. Let each component do one thing well.

That thinking is exactly why thumbhash generation lives where it does.

One important thing to be honest about here is that this setup is not fully failure resilient, and that is intentional.

If the thumbhash function fails today, there is no automatic retry mechanism. Making this fully reliable would require more infrastructure: a queue, retry semantics, possibly dead letter handling, and something like Redis or a managed queue service. All of that is doable, but it also adds operational overhead and complexity.

For this use case, that trade off did not feel worth it. Thumbhashes are an enhancement, not a requirement. If one fails to generate, the image still exists, uploads still work, and the system remains correct. Choosing not to add retry infrastructure here was a conscious decision to keep things simpler and cheaper.

Sometimes not building something is also an architectural choice.

How the frontend uses thumbhash

On the frontend side, thumbhash is used purely as a visual placeholder.

When media metadata is available, the frontend checks for a thumbhash. If it exists, it decodes the base64 string into a soft, blurred placeholder and renders it immediately. The actual image loads on top of it once the network request completes.

This helps avoid empty gaps, reduces layout shifts, and gives users immediate visual feedback, especially on slower connections.

Thumbhash works particularly well with a masonry style image layout, where images have different dimensions and load at different times. Instead of content popping in unpredictably, the layout feels stable and intentional from the start.

I am still finishing this part of the frontend, but it should be live by the time this blog is published.

If you made it this far, thanks for sticking through a fairly deep dive into what looks like a simple feature on the surface. This blog was as much about thinking through trade offs as it was about implementation.

If it helped you rethink how you approach uploads, background work, or system boundaries, then it did its job. For me this was something different to write about 470 lines of blog with seemingly zero lines of code and more about theoretical discussion!

Thank you for reading! 😺